Immigration Detention in 1913

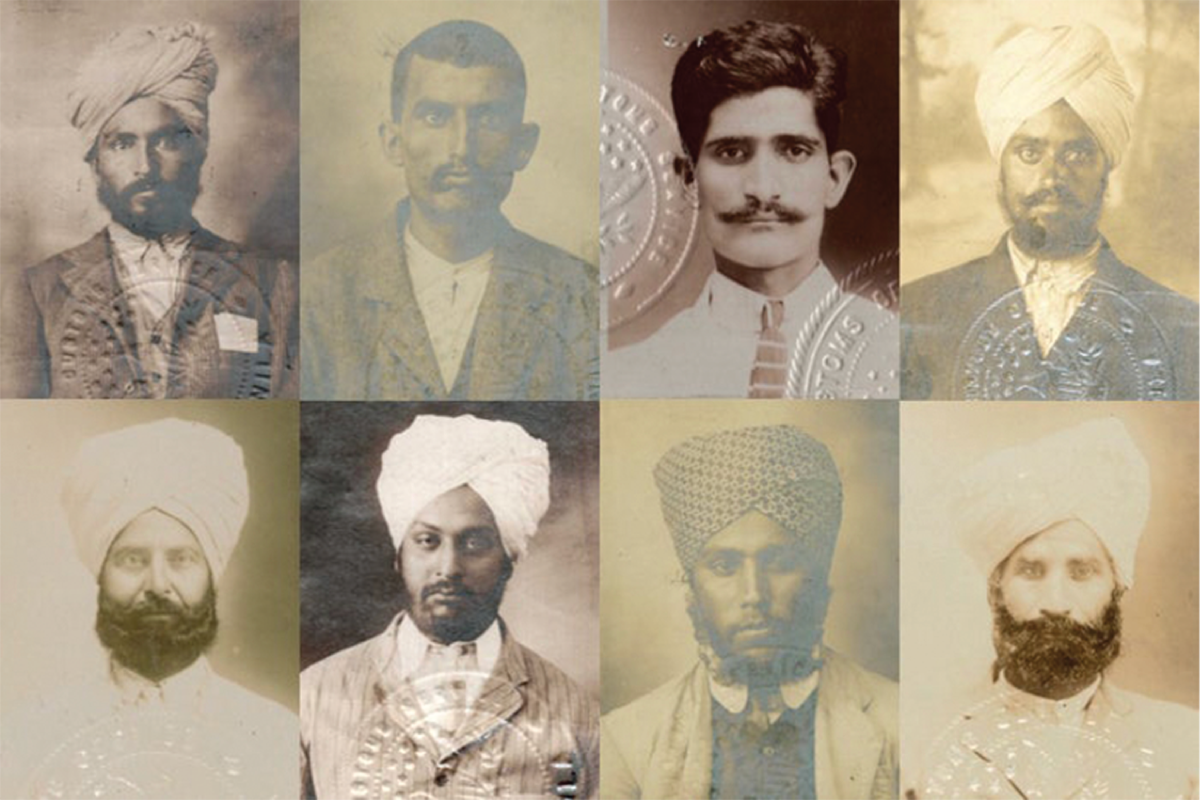

On July 29, 1913, thirteen men from the Punjab province in British India arrived at the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco aboard the steamship S.S. Persia. A few days later another group joined them, bringing the total number to twenty-two.

The men had each secured a Form 546 from the U.S. Immigration Service in the Philippines ensuring their entry into the country. However, upon arrival, they were interrogated by immigration officials and subsequently detained and arrested.

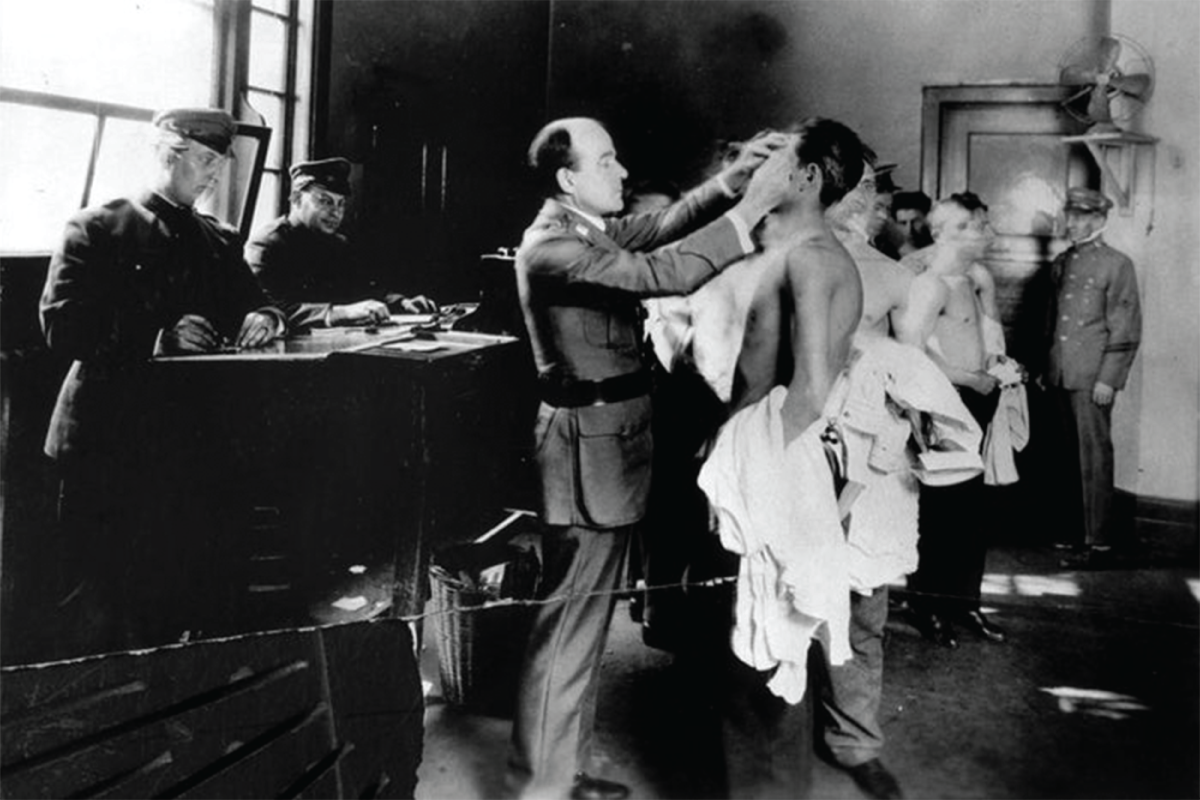

This was a time of heightened anti-Asian sentiment in the United States, and the Immigration Bureau would use various approaches to rejecting South Asians (deemed “undesirable aliens”) from seeking entry into the country.

One was by claiming that they were likely to become “public charges,” unable to find work due to the “strong prejudice against them.” Another was by diagnosing them with uncinariasis, or hookworm—a “dangerous, contagious disease” and a threat to public health in America.

Despite their precarious status in the country, the nascent South Asian community rallied around the detained men. A telegram arrived in San Francisco from Mandhi Khan, in Jungo, Nevada—most likely a laborer in the area’s silver mines. It read:

“If Ghulami[,] son of Butta[,] village of Garhshanker[,] in quarantine[,] please let him out[.] If you want bonds[,] fifty men here responsible for this man will give bonds for any sum required[.] Do not return him[.]”

Thus commenced a lengthy legal tussle that dragged on through the federal courts of northern California for the next two years. Finally, in March 1915, the twenty-two men had their case heard by the Circuit Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. It was not in their favor.

What happened to these men next is not entirely clear. But on March 6, 1917, almost four years after they first arrived at Angel Island, the Department of Justice admitted that it had been wrong in detaining the twenty-two men and withdrew all relevant cases.

“The Department of Justice today notified. . . that it would file on March 6 with the Supreme Court a ‘confession of error’ in the stand taken four years ago when 22 Hindus on arrival here were ordered deported.”

In writing his essay for TIDES, Sharmadip Basu reconstructed this history using the Angel Island immigration case files, which you can read in SAADA.

Basu writes:

"These papers offer us a fascinating time-lapse view of successive episodes in the case of twenty-two Hindus. We see up close the various executive and legal investments at play around the issue of Hindu immigration at the time. We see how the regulatory apparatus of immigration, at its highest echelons, was driven explicitly by anti-Asian/anti-Hindu racism. Most illuminatingly, perhaps, we also get dense biographical snapshots—captured under tenuous circumstances of an immigration interrogation, mediated by a translator—of those Punjabi migrants arrested and detained at Angel Island. From these transcripts, we get to know how old they were, which village they came from, their marital status, how much money they had, other places outside the subcontinent they had been to, and so on. Indeed, the Angel Island case files lift these otherwise faceless, anonymous figures of history to its surface, like bubbles that then disappear somewhere in the West Coast of early-20th century America."